02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Friday,

14

November,

2014

Friday,

14

November,

2014

Friday,

14

November,

2014

Friday,

14

November,

2014

The sacking of Irakli Alasania, Georgia’s Defense Minister since October 2012, sent shock waves through the country’s political system. But it should not have. After all, Alasania is one of 9 incumbents in this key ministry since 2004. Moreover, with 2 years and one month in office, he is tied for second place with David Kezerashvili as the longest-serving Minister of Defense after Bacho Akhalaia (2 years and 11 months). Fourth on the list is Irakli Okruashvili (one year and 11 months). All other ministers served between 3 and 8 months.

Neither should Alasania take offense with PM Garibashvili’s calling him “reckless, foolish and ambitious”. All his long-serving predecessors in office fared much worse. Akhalaia is currently serving a 3-year term in prison. Kezerashvili was detained in France in early 2013 on multiple criminal charges and escaped extradition by the skin of his teeth. Okruashvili was sentenced in 2008 to an 11-year prison term in absentia. The last minister of defense under Shevardnadze, a civil war hero and martial arts specialist Davit Tevzadze had to battle corruption allegations back in 2004 and completely retired from public life. Dimitri Shashkin, the last minister of defense under Saakashvili, chose to weather the 2012 political storm in voluntary exile.

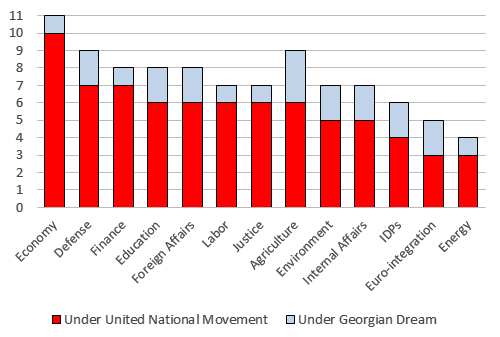

As a matter of fact, the degree of reshuffling plaguing the Ministry of Defense is not all that special in Georgian politics. As shown in Figure 1, all other ministries have seen frequent changes in leadership. In fact, the ministry with the least continuity at the top – and no sustainable leadership until October 2012 – has been the Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development. Since 2004, this ministry has had 11 individuals serving that role, ranging from heavyweights, such as Kakha Bendukidze, all the way to featherweight Vera Kobalia.

Figure 1. Number of ministers, by the ministry, since the Rose Revolution

Full data on the Ministerial Turnover is available here

Georgia clearly stands out in the degree of political change and ministerial reshuffling compared to its immediate environment. To begin with, Georgia is the only country in the region to go through an orderly democratic transition in 2012. But Georgia is worlds apart also when it comes to mobility in top ministerial jobs.

Both Armenia and Azerbaijan see much less rotation within their political power structures. Azerbaijan is perhaps an extreme case since most Azeri strongmen have been holding to their positions since the mid-90s on the basis of personal allegiance and family ties to the ruling Aliyev/Pashaev clan. For example, Safar Abiyev served as Azerbaijan’s minister of defense for more than 17 years (1995-2013). Kamaladdin Heydarov (allegedly one of the richest Azeris) has been holding financially lucrative positions as head of State Customs Committee from 1995 till 2006, and Minister of Emergency Situations since 2006. Winds of change started blowing very recently with a few long-serving ministers (defense, economy and industry, agriculture, education, communication, and high technology) stepping down and letting new blood into the system.

The situation has been quite a bit more dynamic in Armenia, which has had three presidents since independence – Levon Ter-Petrosyan (1991-1998), Robert Kocharian (1998-2008), and Serzh Sargsyan (since 2008). Sargsyan, Armenia’s current president, was the country’s defense minister for a total of 9 years (1993-95, 2000-2007) and has held other top security-related posts in between. His successor, Seyran Ohanyan, is heading up the Ministry of Defense since 2008. In fact, the vast majority of Armenia’s current ministers have been in office since the 2008 presidential elections, which can be considered the norm in most democratic countries around the world.

In economics, it is common to represent the relationship between possible rates of taxation and the resulting levels of government revenue by means of the so-called Laffer curve. The idea is very simple: if the tax rate is set at 0%, the government will not be able to collect any revenue; the same is true, however, if the government sets the tax at 100% (since nobody will have any incentive to work). A conclusion from this simple analysis is that there is some medium level of tax (not necessarily 50%!) that maximizes government revenue.

One can apply the same logic to rotation in top political jobs and quality of governance. Zero or close to zero turnovers (Azerbaijan-style) is clearly suboptimal. It prevents new people and ideas from bearing on decision-making, fosters corrupt networks and clientele politics. Georgian-style carousel, however, also leads to suboptimal outcomes. Ministers cannot be expected to make the right choices if they are replaced before they get a chance to learn the name of their secretary, let alone acquire a good sense of the sector they are in charge of (be it defense, foreign relations, agriculture, the economy as a whole, or education).

Compared to Armenia and, particularly, Azerbaijan, Georgian politics are extremely young and volatile. Over the last decade, Georgia has had eight heads of government, from Zurab Zhvania to Irakli Garibashvili (six of these served under Mikheil Saakashvili in 2004-2012). Headed by 32 y.o. Irakli Garibashvili, the current Georgian administration clearly lacks experience in both policymaking and politics. This is reflected in the quality of decision-making (think how many new legal acts and regulations had to be put on hold or reversed in recent years and months), impatience (to get things done and with each other), and rhetoric (Exhibit A: Garibashvili’s public remarks on Alasania’s character).

Figure 2. Percent of ministers changed, Georgia, 2004-2014

Figure 2 shows the % of ministers changed every year since the Rose Revolution of 2003. Given that the number of ministries varied over time from 22 to 17 (quite a few ministries have been liquidated following the Rose Revolution) this is the correct measure of instability in the top government jobs.

With two more months to go, the degree of ministerial turnover in 2014 has reached an alarmingly high level of 60% – the highest in Georgia’s recent history, excluding the three election years (2004, 2008, and 2012). In particular, it is higher than in 2007, a year that saw the beginning of mass protests against UNM rule. While certainly indicative of a crisis, Alasania’s departure does not signify any change in Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic orientation (despite UNM and Alasania’s attempts to claim so). Rather, it adds to Georgia’s growing pains as a fledgling state and democracy.

Every cloud has its silver lining and, like many observers, we find some comfort in the fact that the new Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tamar Beruchashvili, is no newcomer to policymaking and politics. The appointment of this seasoned career diplomat, who has for years handled Georgia’s relations with Europe, suggests that Georgia’s political system is slowly but surely gaining in strength and maturity.