24

April

2024

24

April

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Friday,

20

March,

2015

Friday,

20

March,

2015

Friday,

20

March,

2015

Friday,

20

March,

2015

“Roulette until six in the evening. Lost everything”, notes Leo Tolstoy on July 14, 1857. He did not pen these words in Moscow or St Petersburg”, writes Elizabeth Neu. “It was in Baden-Baden that Tolstoy closed his diary with a sigh that night.”

“Tolstoy was not the only literary genius to have traveled thousands of miles from Russia to take the waters and enjoy the thrill at the roulette tables… and to leave with empty pockets. They all flocked here: the great realist Ivan Goncharov and the enthusiastic young ballad rhymer Vasili Zhukovsky. Nikolai Gogol came too and observed that “nobody here is seriously ill. They only come to amuse themselves.”

The Russian craze about Baden-Baden survived for more than two centuries – apparently, ever since Princess Louise of Baden’s marriage to Alexander I in 1793 – thanks to Russian literary giants who flocked to this spa town and made it the setting of their novels. The town’s hot springs, luxury hotels, horse races, and, of course, the casino provide the context for Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, Turgenev's Smoke, and, perhaps most famously, The Gambler by Dostoevsky. And, as 19th-century classics continue to be widely read in Russia, Baden-Baden remains a destination of choice for Russian tourists of today.

The same Alexander I is signed on a decree (1803), paving the way for the development of mineral water resources and the establishment of spa resorts closer to home, in the newly acquired areas north of the Great Caucasus range. It took another 20 years and considerable investment in public infrastructures such as roads, parks and boulevards, baths, and hotels for spa towns to spring up and flourish in the Caucasus Mineral Water zone established by the Tsar.

Reflecting this development, another famous 19th-century Russian classic, A Hero of our Time (1840) by Lermontov, is set in the spa resort of Pyatigorsk (where Lermontov found his death in a duel only a year later). Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita contains references to Narzan – a premium mineral water bottled in Kislovodsk since 1894, which happens to be the main rival of the Georgian Borjomi on the former Soviet Union market.

Georgia itself appears on the Russian spa tourism and mineral water map in the late 1820s, with the discovery of Borjomi springs by a Russian army unit stationed in the eponymous valley. The brand’s further history is closely associated with the Tsar’s family, which financed the construction, in 1850, of a mineral water park, and commissioned the first bottling plant. With Borjomi water gaining recognition, the government began building palaces, parks, and hotels to accommodate visitors, including members of the royal family and Russian culture greats such as Anton Chekhov, and Piotr Tchaikovsky. The opening of the Khashuri-Borjomi railroad (1894) provided a further impetus, shortening travel time to Tbilisi and allowing for the launch (in the same year) of a bottling plant by the Governor-General of Caucasia, Grand Duke Mikhail Romanov (incidentally, married to Princess Cecily Auguste of … Baden).

Located about 7km from Kutaisi, Tskaltubo is by far the largest spa town south of the Great Caucasus Range. With its development beginning in 1925, Tskaltubo owes its existence not to Russian monarchs, but to Soviet planners. In 1931, a decree by the government of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic designated Tskaltubo as a premium spa resort and balneotherapy center. Built according to a series of master plans continuously modified and adapted between 1933 and 1983, Tskaltubo rises to prominence as an all-Union spa resort around 1955. By the end of the 1980s, it becomes a top tourist destination serving the entire USSR market. Conforming to the Stalin era’s urban planning and neoclassicist architectural designs, Tskaltubo’s 22 sanatoriums (a total of 5,800 beds) form a circle around a once beautiful park, recreation, and balneology facilities. A daily Moscow-Tskaltubo train provided a low-cost transportation option for thousands of tourists and patients from all over the USSR.

The efforts to develop Georgia as a major tourist destination appear to have stalled in recent months. The number of international arrivals to Georgia, which has been doubling every 3 years between 2003 and 2012 (a stunning pace!) has not grown in 2014. Data for the first two months of 2015 even suggest a decline. While the number of “tourists”, as opposed to truck drivers and other “travelers” transiting through Georgia, did increase by about 7% in 2014, this does not change the fundamental fact that Georgia’s tourism industry is losing great momentum it had enjoyed up until 2014.

Several factors combined reduce Georgia’s attractiveness as a transit corridor and tourism destination. First and foremost, Georgia is affected by the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, two of its major trade and tourism partners, as well as the drastic (but hopefully temporary) reduction in car re-exports to Azerbaijan. Second, however, Georgia’s future as a tourism hub is clearly not helped by the recent changes in visa and migration policies. Georgia’s first National Competitiveness Report (NCR 2013) proudly dwelled on the country’s stellar record in lifting restrictions on travel to and through the country.” In particular, the report goes, Georgia “has no visa regime with almost 90 nations; citizens of most other countries can be issued visas (and, until recently, also bottles of wine!) at the border.” Well, things got quite a bit more complicated since September 2014.

But, and this is a key question to ask, should we really be all that concerned with the overall number of international arrivals, or even tourists?

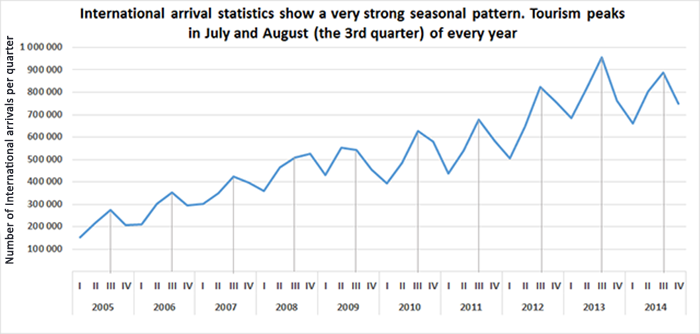

One thing to note is that foreign arrivals are extremely concentrated in a very short period around July and August.

While creating seasonal jobs and bringing foreign currency, such a sharp seasonal peak in mass tourism carries many negative externalities by straining the environment and creating congestion. The highly pronounced seasonal pattern also negatively affects the hospitality industry by reducing incentives to invest in physical capital and skills (which remain idle or underemployed for 10 out of 12 months).

Thus, the Georgian government should be advised to worry NOT about the sheer number of international arrivals, but rather about the number of tourists visiting the country in the offseason period. And this is precisely where Tskaltubo, as well as Sairme and other spa resorts, fit in.

Let there be no illusions. The natural market for Georgia’s spa services is not Western Europe or North America. Relatively wealthy Western European and American tourists account for a meager 3% of all international arrivals to Georgia, and few, if any, of them are aware of Georgia’s potential in balneotherapy or the great curative qualities of Borjomi and other Georgia’s “strangely tasting” and “salty” waters.

The real market is the former USSR – Central Asia, Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus – for which Georgia and the Caucasus will be forever covered by a shroud of mystery. The experience of Sairme, a spa resort brought back to life in 2012/13 through a Public-Private Partnership involving the World Bank and a private Georgian business, proves this point. Sairme enjoys a steady stream of visitors from Kazakhstan and has been actively pursuing other Eurasian markets. It does not have the resources to invest in a massive marketing campaign outside the CIS.

Tskaltubo, Borjomi/Bakuriani, Akhtala, and other water and mud spa resorts are now being seen in Tbilisi as the next big thing in the development of Georgia’s all-season tourism industry. Having commissioned master plans and marketing “teasers”, the government is currently on the lookout for foreign and domestic investors interested in the sector. A must-see interview with Keti Bochorishvili (a Deputy Minister of Economy and Sustainable Development) at the MIPIM 2015 Expo, provides a good idea of the Georgian government’s approach and message in this regard.

There are many aspects of the hospitality and tourism industry that create so-called scale effects and threshold effects. For example, a minimum number of daily users is needed to justify investment in a modern ski lift; a resort location must have at least 800 beds to be able to engage a major travel agency; a minimum number of regular passengers is required for a commercial airline to offer a new route. Private investment in hotels and other tourist amenities must be synchronized with public investment in infrastructures such as air and ground transportation, communication, water, and sewage systems.

Tskaltubo is a classical case in point. On the one hand, the resort benefits from improvements in the national transport infrastructure – the new Kutaisi airport, the expected upgrading of the railway system, and the East-West highway. Yet, a major effort would be required to synchronize the actions of individual investors in the renovation of existing sanatoria (the majority of which are lying in ruins) and the construction of new amusement parks, shopping centers, casinos, and other essential amenities. Given how interconnected everything is, potential investors and the government are locked in an all-or-nothing situation. Hence, the challenge and the great opportunity.