02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

18

December,

2023

Monday,

18

December,

2023

Monday,

18

December,

2023

Monday,

18

December,

2023

As Georgia advances on its path toward European Union (EU) candidacy, the anticipated economic benefits, increased foreign investment, and alignment with European standards present a promising trajectory, worthy of further attention within the following article. The granting of European Union candidate status is a significant political signal, one which represents an initial step towards acknowledging that a candidate country is on the path towards eventual EU membership. In the next pivotal step comes the launching of pre-accession negotiations, accompanied by access to pre-accession funds, which serve as a strategic investment both in the enlargement of the region and for the EU’s future. These funds play a crucial role in supporting the country and its institutions as they undertake essential political and economic reforms, thereby aligning themselves with EU standards and obligations. Their overarching objective is to provide citizens with enhanced economic, social, and political opportunities and to establish high standards of living, the equivalent of those enjoyed by EU citizens. In addition, pre-accession funds contribute to the EU’s broader objectives, which encompass sustainable economic development, energy security, transportation, environmental sustainability, climate change, and regional stability.

The journey towards EU membership also involves lengthy negotiations where candidate countries must adopt democratic norms and implement reforms to comply with EU rules and regulations across various policy areas. These negotiations are structured into “chapters,” each representing a distinct policy domain. A candidate can only conclude a chapter when the EU member states agree that the necessary criteria have been met. While final admission to the EU occurs when a candidate country is deemed to have successfully concluded each of these chapters, requiring unanimous approval from all EU governments.

Candidate status thus opens opportunities for a country to transition from neighborhood policy to fall under the enlargement policy. The accession process officially begins when all EU member states collectively support the decision to initiate negotiations. This decision, primarily political in nature, varies in duration in each case. Throughout the negotiations, the candidate country is tasked with aligning its legislation with EU law and implementing comprehensive reforms spanning political, social, economic, judicial, and administrative domains. Therefore, discussions regarding the timing of Georgia’s EU accession should consider the unique circumstances of the country.

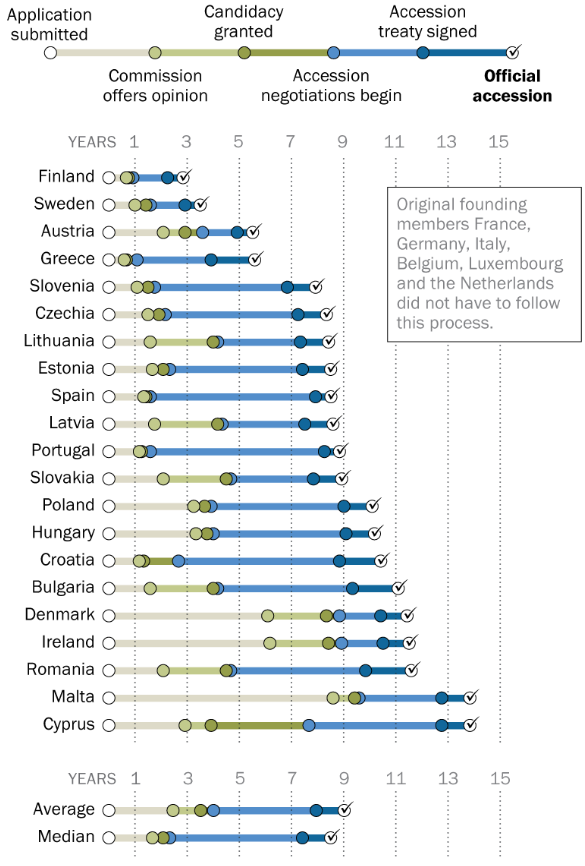

Reaching candidacy status for EU membership typically involves a process that spans several years. On average, it took around 3.5 years for current EU members – from the formal application submission to approval by the European Council. After obtaining candidacy, the next step on a country’s accession path is commencing pre-accession negotiations. Based on the experience of other countries thus far, an average of nearly two years is required from receiving candidate status to the start of negotiations (Figure 1.). However, for Albania, it took almost six years to commence accession negotiations, and North Macedonia took more than 15 years from candidate status to reaching these negotiations.

Beyond its political implications, attaining candidate status holds a significant economic impact. The candidate country gains access to vital EU financial instruments during the accession process, thus facilitating the alignment and implementation of EU legislation. In essence, candidate status itself serves as a powerful political catalyst, propelling deep transformations across all sectors and fostering greater integration into the EU common market. Increased access to financial resources from the EU includes access to instruments such as the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA III), which facilitates socio-economic investments in candidate countries. The anticipated economic benefits extend to increased foreign direct investment (FDI), aligning with historical trends observed in other candidate countries. The geopolitical context and unique circumstances in Georgia underscore the need for a nuanced approach, potentially involving innovative reconstruction mechanisms. As Georgia advances toward EU candidacy, the reforms outlined and the financial support will not only contribute to its economic growth but also pave the way for enhanced regional integration and resilience.

Figure 1. A typical timeline of EU accession

Source: PEW Research Center

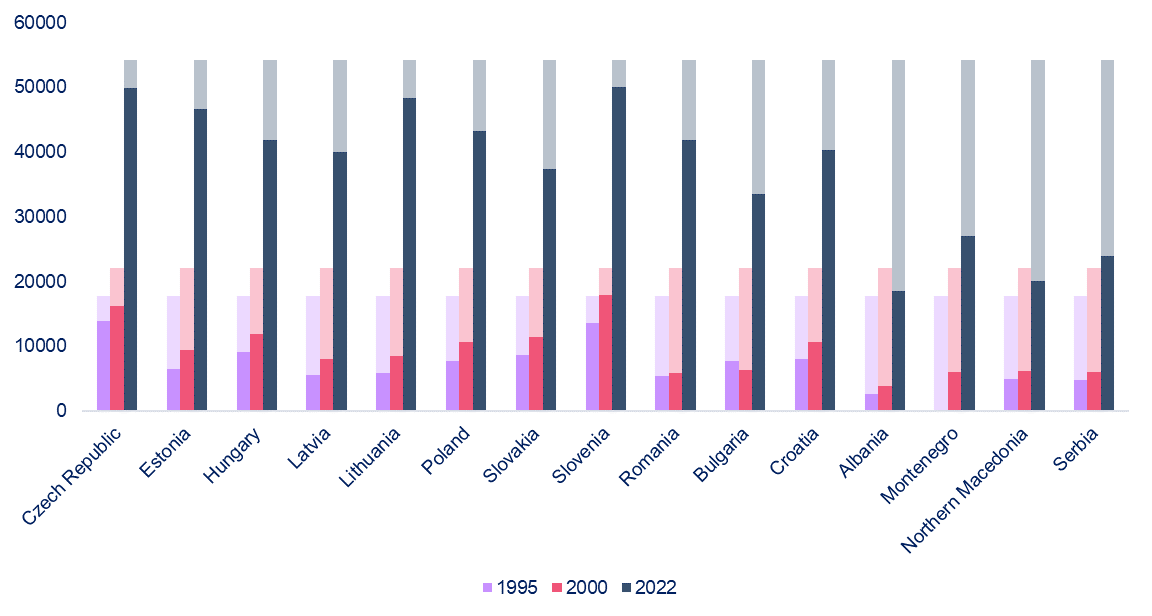

The benefits of granting EU candidate status may vary from political, security, and economic benefits. Although the status primarily carries purely political value, it could also offer an economic advantage to its holder. Countries under the enlargement umbrella have greater access to the financial sources provided by the EU. During the candidate status period and after accession the difference between EU per capita GDP (PPP) and the candidate states’ same parameters is particularly noteworthy (Figure 2). This is predominantly because the institutional and economic reforms the EU requires from candidate countries represent the foundation for fostering economic growth and high standards of living.

Figure 2. GDP Per Capita vs EU GDP Per Capita (PPP)

Source: World Bank

There are various benefits derived from EU Financial Instruments. For instance, economically, candidate status offers access to these instruments, including the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA III). Previously, Central and Eastern European countries utilized various funding programs for membership. At present, the IPA III, designed for 2021-2027, focuses on socio-economic investment in candidate countries. It accounts for more than 14 billion euros and is allocated across several IPA facets: 15% for the rule of law, fundamental rights, and democracy; 17% for good governance, good neighborly relations, and strategic communication; 42% for the green agenda and sustainable connectivity; 22% into competitiveness and inclusive growth; and 4% for territorial and cross-border cooperation. The IPA III is aligned with the “Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans”, where the objective is to stimulate the region’s enduring economic recovery, facilitate a green and digital transition, and promote both regional integration and alignment with European Union standards. The Economic and Investment Plan outlines a considerable investment package, channeling up to €9 billion in funding for the region. This initiative aims to bolster sustainable connectivity, enhance human capital, foster competitiveness and inclusive growth, and facilitate a dual transition towards both green and digital advancements. The financial aid provided during the candidacy period for Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Western Balkans, Albania, and Turkey has currently reached 513 million euros.

Aside from candidacy providing access to IPA funds, Georgia already benefits from the EU Neighborhood Development and Cooperation Instrument (NDICI). From 2021-2024, the expected funding amounts to 340 million euros – covering the economy, institutions, the rule of law, security, environmental and climate resilience, digital transformation, gender equality, and building an inclusive society.

Access to long-term loans, grants, and individual EU economic assistance programs further enhances the economic prospects. For instance, the total EU FDI in Georgia reached 819 million euros in 2022. Moreover, after its introduction in 2021, the Economic and Investment Plan (EIP) for the Eastern Partnership has the objective of raising €17 billion in collaboration with international financial institutions by 2027. Within the framework of the EIP for Georgia, the EU has already secured €1.7 billion in investments, including €194 million in grants.

In particular, the key investments involve:

Additionally, between 2021 and 2023, a total of €62.75 million was mobilized under the European Peace Facility to help strengthen the Georgian Defence Force’s medical, engineering, and logistics units. The EU continues to support Georgia through the European Union Monitoring Mission (EUMM) as well.

Furthermore, alongside integration, there are signals for Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). The empirical evidence suggests that foreign direct investment experience a historical upswing during European Union integration, particularly following the accession phase. This trend has been substantiated by various scholarly works, including research conducted by Bruno, Campos, and Estrin (2020). Utilizing a structural gravity framework and analyzing annual bilateral FDI data spanning nearly every country worldwide from 1985 to 2018, their findings indicate a substantial increase in FDI inflows to the host economy following EU membership.

Specifically, their research reveals that EU membership, approximately, leads to a 60% higher influx of FDI from non-EU sources, and roughly a 50% increase in intra-EU FDI. Notably, the impact of EU membership on FDI is demonstrated to surpass that of membership in other regional groups such as NAFTA, EFTA, or MERCOSUR. The research moreover emphasizes that the Single Market plays a pivotal role in driving this differential impact, positioning it as a cornerstone for the observed substantial increase in FDI associated with EU membership.

Remarkably, the impact of EU integration on foreign direct investment (FDI), even in the candidacy phase and at the start of negotiations, manifests through both direct and indirect effects. The direct effects predominantly revolve around considerations of investor risk. According to Bevan and Estrin (2004), the EU effect on FDI operates in two key ways: (1) EU integration provides opportunities for older member states to relocate to applicant countries with lower labor costs, and (2) integration contributes to a reduction in country risk.

In their study, Bevan and Estrin (2004) examined three distinct groups of countries from 1994 to 2000: those satisfying the Copenhagen criteria for EU admission and commencing negotiations (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, and Estonia); those evaluated by the EU as making good progress and likely to be invited to initiate negotiations (Slovakia, Latvia, and Lithuania); and those not deemed to have made sufficient progress (Bulgaria and Romania). Their findings underscored the significant impact of the EU integration announcement on FDI flows between investor and host country pairs.

However, it is essential to note that, while statistically significant, the added explained variance attributable to the inclusion of EU enlargement variables was relatively small — around half a percentage point. This suggests that although the EU integration announcement had a discernible effect on FDI flows, other factors beyond EU enlargement variables also contributed to the overall explanation of FDI patterns during that period.

Clausing and Dorobantu (2005) argue that enlargement announcements have a dual impact on candidate countries, influencing both market access and the perceived level of country-specific costs. In particular, they identify three significant EU announcement effects in their study:

In their analysis, Clausing and Dorobantu find that the 1993 announcement is the only consistently significant EU effect across various model specifications. This indicates that countries included in this announcement received more Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) than other countries in their sample. Furthermore, their analysis reveals a broader trend: European post-socialist countries attracted a higher percentage of FDI relative to their GDP compared to the 18 other countries (old EU members alongside Turkey) included in their study. This observation underscores the attractiveness of post-socialist European countries for foreign investment during the period under consideration.

In summation, both studies provide some indication of the direct EU enlargement effect on FDI, but this effect is not as robust (or convincing) as one might expect. Bandelj (2010) suggests that the lack of strong effects found in previous studies on the role of impending EU membership on FDI inflows is largely due to the ignorance of the indirect effect of the EU on FDI.

The argument put forth here is based on the perspective of economic sociologists, who contend that market dynamics are not solely driven by arbitrage outside the social, political, and cultural context. Instead, market activities are deeply embedded in the institutional framework that sustains them. In the context of our discussion, this implies that post-socialist states shape FDI by establishing both formal and informal institutions that actively promote FDI as a desirable economic development strategy and a suitable form of firm-level behavior (Bandelj, 2009). These promotional efforts, in turn, impact the demand for foreign capital by these states, thereby influencing their actual FDI inflows.

The assertion that EU integration influences FDI promotion by host states, subsequently affecting actual FDI inflows, equally aligns with Bandelj’s (2010) findings. The study illustrates that the EU accession process indirectly influences post-socialist states by shaping their efforts to promote FDI as a preferred strategy for economic development and for guiding firm behavior. These state-led initiatives contributed to increased FDI inflows, beyond the conventional risk and return factors.

Further analyses indicate that decisions regarding state FDI promotion are not solely influenced by EU conditionality. Rather they are significantly shaped by specific legacies, such as the initial privatization strategies chosen by countries, the extent of reform during socialism, and the historical trajectory of state sovereignty.

This divergence in experiences suggests that the dynamics of investment attraction during the integration process can vary, with some regions experiencing notable investment growth even in the initial stages of candidacy. This underscores the importance of considering the unique circumstances, policies, and strategies employed by different countries in their pursuit of EU integration and the associated economic benefits.

Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova present a unique scenario in comparison to previous enlargements due to the current geopolitical situation. Drawing from the experiences of Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, it may appear that the prospect of attracting investment after negotiations is distant for Georgia, especially considering its early stages of integration and the anticipation of candidate status. However, the contrasting example of the Western Balkans, currently under candidate status, showcases a scenario in which investment growth is observable in the early stages of EU integration.

Beyond serving as a political signal for substantial transformations in candidate countries, security within the investment destination holds paramount importance for investors. Notably, examples from the Czech Republic and Romania reveal significant investment growth in the years of their NATO accession (1999 and 2004, respectively), while Poland and Romania experienced investment growth in the year following their alliance with NATO (2000 and 2005, respectively). Therefore, the existing geopolitical circumstances (Russia’s war in Ukraine and potential threats to Georgia and Moldova) are expected to impede Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova from realizing their full potential in terms of attracting investment.

These historical instances underscore that security considerations, coupled with the broader political and transformative signals, play a pivotal role in shaping investment dynamics during the integration process.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of broader trends, it is important to examine the specific parameters for various countries during their candidacies. For example, following the acquisition of candidate status, Croatia experienced an average 18% rise in exports from 2004 to 2008. This increase was particularly noticeable in heightened exports to the EU.

Similarly, exports to the EU for Bulgaria showed an average growth of 23% during their candidacy years. Taking a closer look at Bulgaria, from obtaining candidate status to their official accession in 2007, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows surged almost eightfold. Notably, the credit ratings from S&P for both Croatia and Bulgaria also improved during their respective candidacy periods. Croatia saw an improvement from BBB- in 2004 to BB+ by 2013, while Bulgaria’s credit rating progressed from B in 2000 to BBB+ in 2006. However, such an effect is less visible for other Western Balkan countries after receiving candidate status. For instance, Albania’s FDI grew on average by 2.2% yearly from 2014 to 2022. While the credit ratings from S&P improved only marginally, from B to B+ (2023). Serbia’s FDI flows grew, on average, by almost 12% annually, and the S&P credit ratings improved from BB- to BB+ (2012-2022). These improvements regardless underscore the enhanced economic stability of both countries, creating favorable conditions for increased investment.

Such examples illustrate that candidate status, coupled with different institutional and economic reforms, can bring economic benefits for countries even before accession to the EU. However, as noted, this approach cannot be generalized, and outcomes may vary for individual countries. Where some countries experience a high boost in FDI inflow, export to the EU, or surges in credit ratings, the benefits for other nations can be moderate. Everything therefore depends on how eager countries are to develop their economies and institutions according to EU experience.

In summary, attaining EU candidate status places Georgia on a trajectory toward formal EU accession, instigating widespread reforms, and unlocking economic benefits through financial instruments and heightened foreign investment. The distinctive circumstances, occurring amid conflict, may necessitate a unique approach to accession, potentially entailing unprecedented mechanisms for Georgia’s reconstruction concurrent with the EU preparations for membership.

CONCLUSION

European Union investment facilitation and financial support highlight the shared commitment to fostering sustainable development, facilitating green and digital transitions, and promoting regional integration. The recent decision of the European Commission to grant Georgia candidate status is therefore a significant milestone, indicating progress in addressing the outlined priorities. As Georgia advances in democratic consolidation and economic development, the journey toward EU accession opens avenues for increased foreign direct investment, access to financial instruments, and the promise of sustained economic growth. It is nevertheless necessary to attain political and economic consolidation in respect to the EU and the local context and to take into consideration the experience of other applicants and member countries.

Bandelj, N. (2009). The Global Economy as Instituted Process. American Sociological Review, 74, 1.

Bandelj, N. (2010). How EU Integration and Legacies Mattered for Foreign Direct Investment into Central and Eastern Europe. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 62, No. 3, May 2010, 481-501.

Bevan, A. & Estrin, S. (2004). The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment into European Transition Economies. Journal of Comparative Economics, 32, 4.

Bruno, R. L., Campos, N. F., & Estrin, S. (2021). The effect on foreign direct investment of membership in the European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59(4), 802-821.

Civil.ge. (2022). European Commission’s Memo Detailing Recommendations for Georgia. https://civil.ge/archives/496656

Clausing, K.A. & Dorobantu, C.L. (2005) Re-entering Europe: Does European Union Candidacy Boost Foreign Direct Investment?. Economics of Transition, 13, 1.

European Commission. (2020). An Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans.

An Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans (europa.eu)

European Commission - Deep and comprehensive free trade agreements.

EU-Georgia Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area | Access2Markets (europa.eu)

European Commission - European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations.

Overview - Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (europa.eu)

European Commission. (2020). Western Balkans: An Economic and Investment Plan to support the economic recovery and convergence.

An Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans (europa.eu)

European Union. (2014). Association Agenda between Georgia and the EU.

Association Agenda between Georgia and the EU | EEAS (europa.eu)

European Union. (2022). The Twelve Priorities.

European Union. (2023). The European Union and Georgia.

The European Union and Georgia | EEAS (europa.eu)

PEW Research Center. (2022). How exactly do countries join the EU?

European Union membership: How countries join, and more | Pew Research Center

TBC Bank Publication. (2023). Waiting for EU membership candidate status.

Waiting for EU membership candidate status (tbccapital.ge)

Wikipedia. (2023, November 28). Potential enlargement of the European Union. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potential_enlargement_of_the_European_Union