31

May

2023

31

May

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Friday,

29

March,

2019

Friday,

29

March,

2019

Friday,

29

March,

2019

Friday,

29

March,

2019

In February 2019, Georgian power plants generated 939 million kWh of electricity, which compared to the previous year represents a 0.5% increase in total generation. On the demand side, consumption amounted to 1,037 mln. kWh, a 2% decrease on an annual basis. Although the negative gap between generation and consumption decreased by 22% (from -126 to -98 mln. kWh), compared to the corresponding month of the previous year, it remained substantial. It is worth highlighting, once again, that this negative gap does not wholly reveal the extent of dependence of the Georgian electricity market, as Thermal Power Plants (TPPs), powered by imported gas, provide part of the generated electricity.

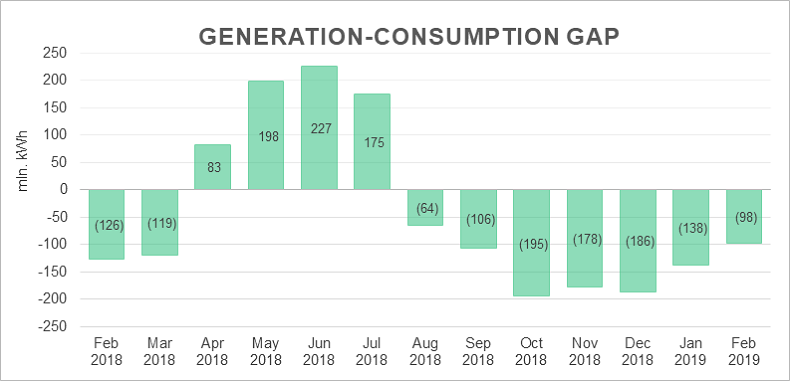

In our previous blog, we mentioned that Georgia has been facing a negative generation-consumption gap since 2017. Looking at the consumption-generation gap over the last 12 months, we can observe a negative gap in all (including August 2018) but 4 months (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generation-Consumption Gap

We have also previously emphasized the need for both supply and demand-side policies, which could ease the burden of increased electricity consumption and decrease generation. One of such was the introduction of the net-metering system by the Georgian National Energy and Water Supply Regulatory Commission (GNERC), in 2016. This policy incentivizes electricity generation from residentially owned, green micro-plants and, equally, reduces the demand for the electricity system from the residential sector. Hence, it can be perceived as a mix of both supply and demand policies. Unfortunately, thus far only 80 consumers have subscribed to the system. In order to increase the number of consumers opting for net-metering and to popularize renewable energy sources, in March 2019, GNERC introduced a new regulation regarding net-metering. The aim of this regulation is to incentivize consumer groups to invest in renewable energy sources,1 such as solar, wind, and water (including wastewater) power for personal consumption and, consequently, reduce electricity expenditure. Such changes enable consumer groups to utilize the electricity generated by a single renewable micro-power plant free of charge and deliver any excess electricity to the distribution network.2 Consumer groups have the opportunity to obtain credits for the excess electricity generated and then either choose to consume or resell the credits. There has also been a change to the connection of the distribution network: if the connection is breached, the connection fee will be halved. Moreover, consumer groups can now acquire temporary ownership of microgeneration power plants, on the basis of tenancy, lease, and/or further contract, in order to make the initiative more affordable.

The key potential benefits of the policy are associated with reduced pressure for demand from the residential sector. Such benefits are developed from increased self-sufficiency and a contribution from the sector to the country’s energy balances (and energy security) in the form of excess residential electricity production. Therefore, if micro-plants are implemented to a significant degree among residential consumers, Georgia will have the opportunity to reduce its dependence on TPPs and foreign electricity imports. Moreover, if micro-plants are implemented near consumption sources additional transmission losses can be avoided and total electricity system losses can be reduced. Finally, the regulation considers the additional environmental benefits associated with the introduction of green energy sources in place of environmentally damaging alternatives such as TPPs.

Not all renewable resources offer the same potential in closing the consumption-generation gap. In Georgia, WPPs seem more likely to fill the gap left by the seasonal performance of HPPs, as wind patterns do not coincide with precipitation patterns, while SPP generation typically coincides with that of HPPs. In some specific cases, however, such as during unusually dry periods of the year, HPPs generation decreases due to a lack of precipitation (as in August 2018), thus SPPs can complement HPP generation. In notably sunny years, generation can be provided by SPPs, whereas HPPs can satisfy most of the local demand during rainy years.

Despite current opportunities, the readiness of the electricity grid system to integrate renewable energy sources, with their fluctuating and less predictable electricity generation patterns, remains a potentially limiting factor to the success of the initiative. Another factor is the risk behind such projects, due to the variable nature of renewable energy sources, although this unpredictability can be lessened by adopting hybrid micro-power plants (wind alongside solar, HPPs alongside solar, etc.)

The regions potentially able to benefit from different renewable energy sources can be identified by looking at climatic, hydro-geological, and atmospheric patterns. For instance, micro-hydropower plants may be an option for villages in the western part of Georgia, as the West has more abundant water resources than the East.3 The regions of Kakheti, Samtskhe-Javakheti, Kvemo, and Shida Kartli all have the potential to develop solar power generation, while Imereti, Kvemo, and Shida Kartli may benefit the most from wind power generation.4 In Tbilisi and other densely populated cities, solar panels may be best suited over other renewable energy sources due to the limited space for alternatives (WPPs, HPPs) and the adverse effects of noise pollution.

The potential benefits for consumers would be reflected in reduced dependence on the current electricity system and less uncertainty in terms of future tariff fluctuations. However, the consumer adoption rate of net-metering is still uncertain, despite the new options introduced by the reform (leasing, tenancy, etc.), due to the high investment costs and the fact that it is often still perceived by subscribers as a risky investment. The rate of adoption depends greatly on the real costs and benefits of the projects, which seemingly cannot be assessed without proper economic knowledge. Subsequently, the residential sector might require more evidence-based support in favor of net-metering, rather than just noting the introduction of changes in the net-metering system, the inclusion of a wider range of beneficiaries, and verbal confirmation of projects’ profitability. In addition, several important challenges might arise from the division of property rights on community-owned micro-plants. According to GNERC, the electricity generated by shared solar micro-plants in multistory buildings could be used for common maintenance, such as for elevators and building lighting, while excess electricity could be divided among households on the basis of private agreements. While in the absence of household cooperation, excess electricity could be divided equally within buildings. These arrangements would require the extension of responsibilities for homeowners’ associations (HOAs) in order to provide maintenance for the micro-power plants, while the representatives of distribution companies would oversee the metering process.

This reform will also have a substantial impact on the distribution companies (Energo-Pro and Telasi) and their subscribers. The combined market shares of these two distribution companies have always amounted to more than 50% of the country’s total electricity consumption, reaching 70% of total consumption in 2018. Ideally, during peak hours, the two companies will be able to reduce pressure by partly decreasing consumption on the system and providing excess electricity to the grid from the residential sector.

Ultimately, the success of the net-metering initiative will depend on:

• the economic profitability of net-metering projects for households

• the success of how well the potential benefits are communicated

• the willingness of residents to participate in community projects

• the readiness of the grid system to integrate renewable energy sources characterized by a variable output

Therefore, despite its undeniable potential as a green and clean solution to the generation-consumption deficit, it is still too early to gauge when net-metering is really going to take off.

1 Consumer groups include apartment owners’ associations, districts, settlements, and villages.

2 The installed capacity does not exceed 100 MW.

3 Approximately 70% of rivers are concentrated in Western Georgia, with the remaining 30% in the East. While the annual river flows amount to 49.8 km3 in the West and 16.5 km3 in the East.

4 It is possible to discern the best locations by inspecting the future investment projects listed by the Ministry of Energy in 2017.